The roads to Zuidas

A journey exploring why I can't call the city I've lived in for 17 years my home

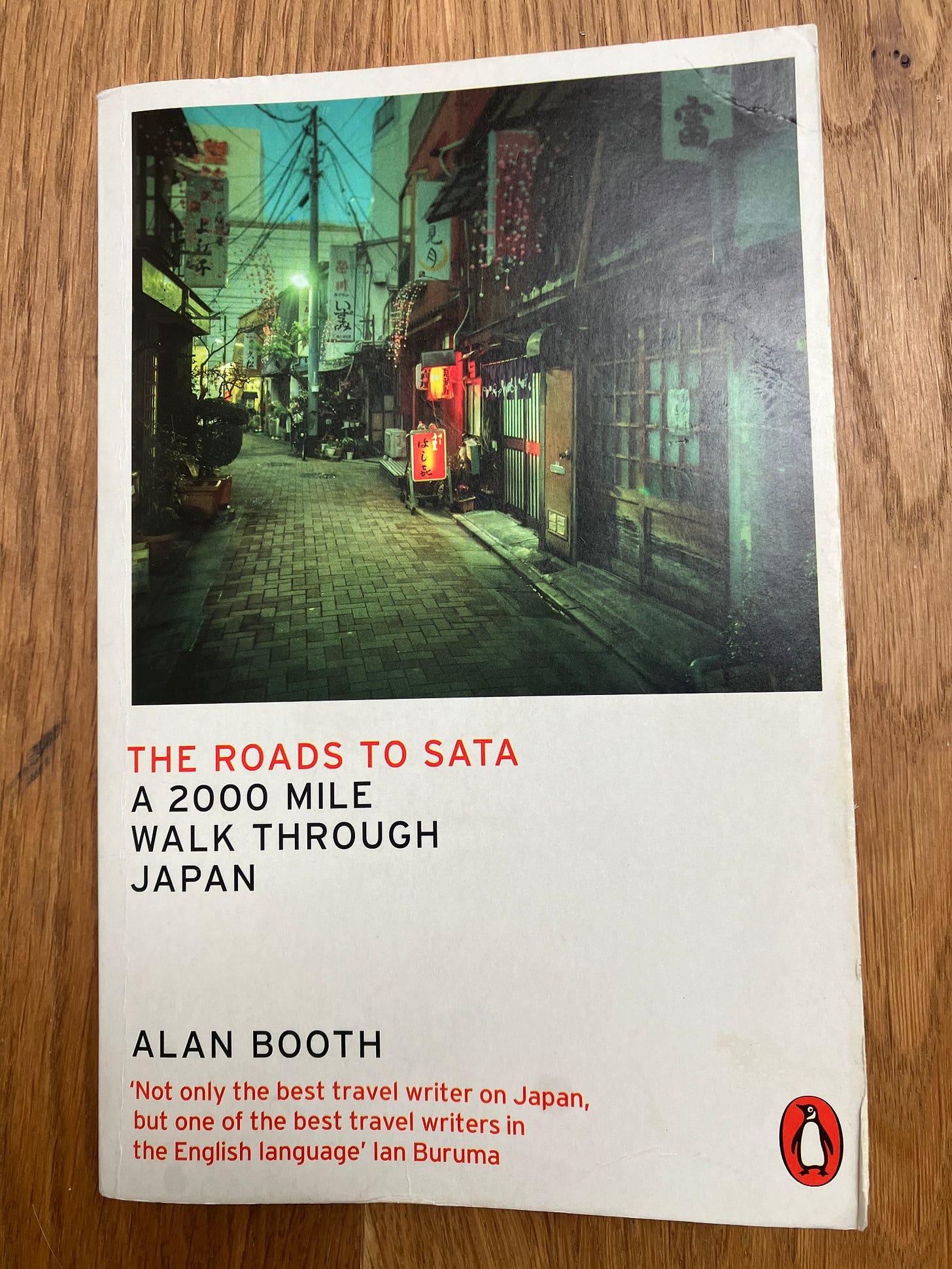

Forty years ago, a book called The Roads To Sata was published. It’s an account of Alan Booth’s walk from one end of Japan to the other, a journey of some 3,250 km. After living in Japan for seven years, Booth wanted to get a clearer picture of the country ‘for better or worse.’ Foreign tourists were a novelty in most of the places Booth traipsed through, and the book provides a revealing portrait of what was still a largely unknown and misunderstood country in the West.

Rereading it made me examine my feelings about Amsterdam. After living here for 17 years, and even writing a guide book to the city, it still doesn’t feel like home. So I decided to follow in Booth’s figurative footsteps and go for a walk to see if I could find out why.

It's grey and cloudy when I set out, just like when I first arrived in the Netherlands. My memory of that day is dominated by the rain that fell upon flat field after flat field we raced past on the journey from Schiphol airport. The rain I could identify with. The scenery left me deflated. I would later learn that the fields are called polders. Even later I would learn there’s a term, polderblind, describing the sensory deprivation caused by looking at the same monotonous landscape for too long.

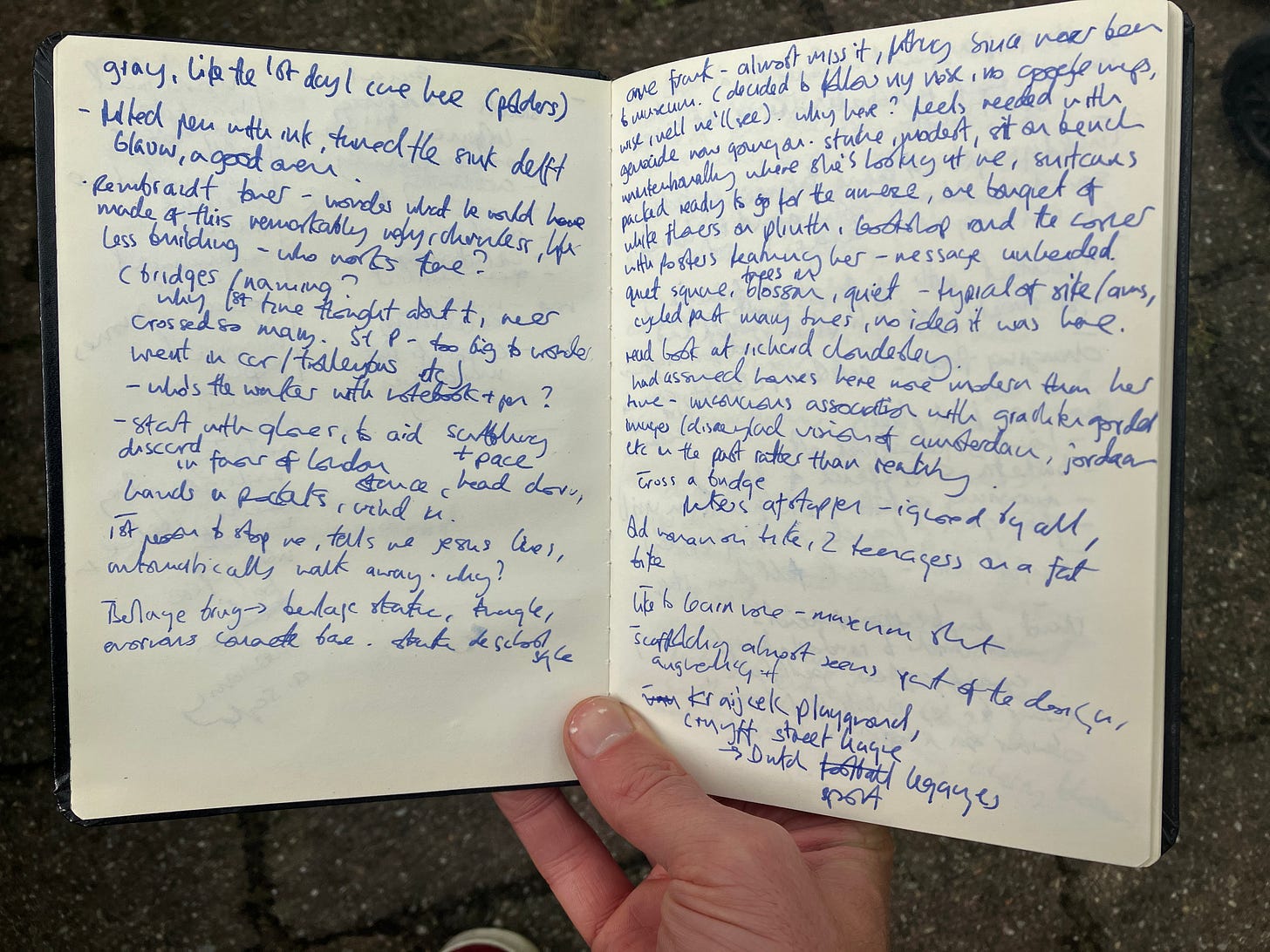

Five minutes into my journey I realise why Booth took a Dictaphone with him rather than the pen and paper I chose. Three of those minutes were spent standing still, writing the insightful notes that would form the basis of this text. In a futile effort to win back time, I pick up my pace only to stop a few steps later at the Rembrandt Tower. Despite its status as the highest building in the city at 135m, it’s a place where only taxis linger: a tall, oblong concrete block that most people rush past on their way to work or the train station nextdoor. To be fair, it does look better at night, if only because you can’t really see it. It’s not clear how the rigid geometry and rampant commercial nature its related to the Dutch master of emotion and expression.

My first non-writing stop is the statue of Amsterdam’s most famous daughter, Anne Frank. Like most of the major tourist attractions here, I’ve never been to the Anne Frank House. I’ve cycled past the building, and the queues that snake around it, countless times but never got close to buying a ticket. As my initial social life here was built around a bunch of Dutch people in their late 20s, museums were neglected in favour of clubs, concerts and bars. Today, however, Anne Frank’s statue is on my way, and offers a belated opportunity to pay my respects.

It’s in Merwedeplein, where the Frank family lived before fleeing to the annexe. On this spring day, Anne stands in the middle of the square, surrounded by blossom, with suitcases packed, ready to leave. Last year, someone wrote ‘Gaza’ on the statue, an act which received predictable condemnation. However, in the face of the atrocities that continue to occur daily in Palestine, the innocence and humanity that Anne Frank has come to represent feel equally tarnished.

One thing Booth never talks about is how to solve the issue of going to the loo on the road. Perhaps it’s easier in rural Japan, but the middle of Amsterdam is a different story. Half an hour into my walk and it’s something I’m worried about already. I enter a square with a large playground with facilities built by two Dutch sporting legends: a street football cage sponsored by the Johan Cruijff foundation, and a playground provided by the (Richard) Kraijceck Foundation. Sadly Dennis Bergkamp hasn’t sponsored a bathroom.

I find myself retracing routes to places I used to live. Walking through the Pijp, I turn onto the first street I lived on in Amsterdam. It was the first of many temporary homes I had in the city, places I moved into while friends and friends of friends went travelling or experimented with living with their partners. These short-term homes ranged from an entire house in the Canal District to a mouse-ridden apartment awaiting demolition. This one in the Pijp was a good one. There was a bay window that the sun flooded through, a dining table big enough to host friends when they celebrated my arrival in Amsterdam, and consoled me when my girlfriend dumped me. A sofa for a colleague to sleep on while he worked in the city temporarily, a ridiculously steep staircase for me to struggle up when drunk. And the best bit was I could stay there for a year. After that two of my best friends moved in, and another friend moved into the flat underneath. She still lives there today. As I approach the building, I decide to venture another breach of Dutch etiquette and call in unannounced. Social visits in the Netherlands are normally planned days, or even weeks, in advance. While kids will often knock on doors to ask if their friends want to play, adults don’t bother. Which given that in Amsterdam most of my friends live at most a 25-minute cycle ride away is a crying shame. Calling my friend doesn’t get off to the best start, mainly because when someone asks where you, and your reply is ‘outside your door’, it’s a bit weird. A good cup of Greek coffee and thirty minutes later, we’re both feeling better about the world. My friend even tells me dropping in is something we should do more often. I’ll try.

With a spring in my step I wander westwards, picking my way alongside a canal. The other side of the street is dotted with red light windows. Even at 10.30 in the morning there are women sitting stoically in the windows, gazing into the distance, anywhere it seems apart from at the men stood equally stoically in front of them, with arms folded and legs planted firmly on the pavement. Nobody moves for the five minutes it takes me to walk up the road.

The sun finally breaks through as I reach Museumplein, the large square on which you can find, well, museums: Van Gogh, Stedelijk, an art collection that tries to pass itself off as a museum (hello, Moco) and the Concertgebouw, the concert hall with the best acoustics in the city. Sunlight adds an extra splash of colour to the cherry blossom under which a small crowd of Japanese tourists are taking selfies. Today, as I have for most of my time here, I skirt the museums, as I have for most of my time here, and veer off towards Vondelpark. This is one of the few places in the city where walking is accepted – as long as you’re accompanied by a dog or baby. My favourite bit of the park is the Sheep Meadow, which lies on the south side, just past the Picasso statue. As it’s rewilded, nobody’s allowed in. There’s rather a fetching straw bee hive, and some grass, and that’s about it. Bees and butterflies buzz around, birds call, ducks quack. It’s only the occasional drone of construction work that drags you back to reality.

I leave the Vondelpark by one of the side exits. It appears I’m wandering towards another one of my old residences again. At the end of my old street is something I’d never noticed before, most probably because I’d never needed it. A urinoir. Aka an open place to pee for men, or desperate women. As it’s the first one I’ve come across one day, I decide to use it anyway. I keep as far away as practically possible from the hole, and try not to think about what all the toilet paper on the floor has been used to clear up.

I head up the Hoofdweg, one of the few straight roads I’ll walk on all day. It takes me past an old workplace in de Baarsjes that I shared with a fashion designer. This was probably the first place in Amsterdam I made real contact with the neighbourhood. As a woman working alone in her studio, the local community adopted her as one of her own, calling her buurvrouw (neighbour) and popping in for regular chats. Most of them were worried that despite renting their homes for more than twenty years, they would be kicked out by their landlords, who wanted to renovate the flats and raise the rent. The landlords would be obliged to rehouse them, but on the outskirts of the city, away from family and friends. I don’t know if they’re still living there now, but the neighbourhood hub that used to be opposite has been replaced by a dog trimming salon. The newsagent on the corner is a speciality coffee and natural wine bar.

One of the things I used to like about Amsterdam was that it never seemed to change. On my visits back to London, I was sad to see that in my absence familiar bars, cafes, restaurants had been and gone. Music venues and cinemas disappeared. The streets I used to know felt different every time I came back, making me feel like the city was moving on without me. And now the same had happened in Amsterdam. The ill wind of gentrification blowing through the city is spreading. My favourite sourdough bakery has now taken over four shops in an arcade. The bread (and chocolate miso cookies) are so good that I regularly cycle the best part of an hour to bring them home. The kimchi and lentil burger I have for lunch on this walk is genuinely one of the best I’ve ever had. But does anyone miss the mobile phone shop that used to be here? The queues of people lining up to make social media films of the admittedly delicious pastries, breads and sandwiches certainly don’t.

In that way it’s reassuring to see that Bos and Lommer, further north, doesn’t appear to have changed as much, even if lots of high-rise buildings have sprung up in the mean time. The same baker is on the corner where I used to get Turkish pizza in the morning after catching the train in from Utrecht to work. On that walk from the station I must have passed the tiny, picturesque village of Sloterdijk countless times. But as with so much I see today, I never paid it any attention. This village, once outside Amsterdam, used to be all fields. Probably polders. A statue, ‘The Extinct Farmer’, is a memorial to the people who worked the earth here for a thousand years before it was swallowed up by the city. Nowadays it’s mainly noticeable thanks to the small spire of the white church. Walking around the narrow lanes encircling the church feels like entering a tiny theme park, another extension of the Disneyland feel that the Canal District can have. But the windows are boarded up and I’m the only person here. The mix of old and new, the surrounding office blocks that dwarf Sloterdijk village, feels almost Japanese in its incongruity.

After five hours of walking, my legs are beginning to tire. It's time to start walking back east. Instead of plodding down the main road, a pass through a volkstuin, a sort of allotment, where people can rent a plot of land and a small house, do some gardening from Spring to Autumn. It’s a great idea, but this one feels a bit too regimented. Each house is in immaculate condition, the grass is perfectly cut and there’s not a white pebble out of place on the paths. As nobody seems to be around it feels more like a cemetery than a breeding ground for flora and fauna. To make matters worse, every path looks the same and I get lost. After going around in circles, well, squares, for twenty minutes, I escape and and follow the train tracks towards Westerpark. Even with the occasional train rushing by, tranquillity reigns, which is remarkable so close to the city centre.

Westerpark is a wonderful park with an old gasworks in the middle. It feels more welcoming than the Vondelpark, with something for everyone. Tennis courts, fields, a farm, a cinema, hotel and a couple of bars are all tucked away inside its voluminous acres. It even offers the novelty of walking uphill if you choose to snake along the north side of the park. Back in the day, it was where I would meet with friends to play tennis and have a drink afterwards or have a birthday party in the summer. As we got older, the same friends started organising an art fair on the terrain, and this year they’ve even opened a museum.

As I enter Haarlemmerweg, the oldest shopping street in the city, I start thinking about beer, one of the recurring motifs in Booth’s daily routine. I’m clearly not the only one, as I bump into a hen party careering down the narrow pavement. Surprisingly, despite the ‘bride to be’ banners adorning their chests, they’re not British but Dutch. I had originally planned to steer clear of the centre by taking a ferry from West to North Amsterdam, and walking all the way back home via a picturesque old fishing village. But my note taking has been so extensive that I have to cut through the centre after all. The closer I get to the heart of the city, shops change from the usual variety of stores and services into a series of adjoining vintage clothing shops, smart shops, coffee shops and indeterminate eateries offering mountains of waffles and pizza slices in the window. I wonder if they ever get eaten. The next day I read that a tea shop that’s stood on this street for more than four hundred years is to close, as the rent is too high. Will it be missed?

The compensation to this route is walking past Central Station, which remains one of my favourite buildings in Amsterdam. Apparently it was built there by the government of Den Haag to slight to their nosy northern counterparts, but I’d argue it’s now the cherry on the city’s cake. When I first moved to the Netherlands, this was my gateway to the city. I’d hop on a train from Utrecht, pass through Central Station, grab a number 1,2 or 5 tram to Leidseplein then catch a show at Paradiso or Melkweg. Since Eurostar has arrived here, it’s now where I get the train back home to London.

Instead of following the river Ij back east behind the station, I veer off the other side towards Entrepotdok, a scenic route through old warehouses and boatyards that offers peace, quiet and a view of Artis zoo. Sadly there are no giraffes or elephants or lions visible on other side of water, nor can I hear any of the monkeys or birds - just a man with a smoker’s cough sunbathing on a balcony.

My pace quickens as I realise I’ll soon be heading down Javastraat, one of my favourite streets in the city. It’s horrible to navigate on a bike, as cars and delivery vans have a tendency to stop suddenly for deliveries and chats, while scooters and other cars weave around them. It’s not much different on the pavement. People walk three abreast, linking arms to block your path. Shops spill out onto the pavement, including a butcher doing a barbecue that floods the street with smells enticing enough to almost attract a vegetarian. It feels alive, like a proper city. The shops are used, food isn’t stored in the windows but consumed with gusto. I walk past the Pakistani shop where I get everything for curries (and juicy mangoes in the summer), the best falafel shop in town, the place my kids get their haircut, and an independent bookshop. My destination is one last park, Flevopark, where a tiny jenever (the Dutch cousin of gin) distillery boasts one of the best beer gardens in the city. Het Nieuwe Diep offers an oasis of peace and quiet, with a small pond, or lake if you’re feeling poetic, in front of a picture perfect cottage. It’s four o’clock, not quite drinking time yet, but as that never seemed to bother Booth, I don’t let it get in my way either.

As I approach the bar, two staff are discussing how intense Italians can be. Finally, I see an opportunity to emulate Booth in connecting with locals. Until now, I’ve only had two conversations with strangers: one wanted to talk about Jesus, the other wanted to buy my hat. It turns out that walking around at a fast pace, frowning in concentration, isn’t a particularly inviting sight. But here, in a bar, with a subject I know about, I feel confident enough to offer my opinion (in Dutch), that Italians aren’t intense, just not as reserved as us North Europeans can be. The conversation continues as my beer is poured. ‘That’s true. But you know who’s really intense? English people.’ My smile falters. The list of intense nationalities goes on, but my mind is elsewhere. Normally my accent is a clear giveaway that I’m not Dutch. South African or German are common guesses about my background. Either way, the assumption is that I’m not English, as our general reluctance to learn other languages means I wouldn’t be speaking Dutch. As my beer, an excellent German Helles, is placed in front of me, I hesitate between making a witty comeback or a barbed comment, but settle for the rather more English response of a weak smile and a polite dankjewel (thank you).

As I sit down with my beer, I contemplate what my day has brought me. Perhaps like my walk today, it’s brought me back to where I started. I’m still not closer to thinking about my place here, or what I’ve learned today. Booth could never be anything apart from a gaijin (foreigner) in Japan. But with my white skin and ability to speak the language, I can pass for Dutch. One woman even told me I had an Amsterdam accent. Which was very kind of her, but sadly rather overestimating my skills. But as my ramblings today proved, I have roots here. I’ve lived or worked, drunk or danced in almost every part of the city, I chose to live and stay here - yet something is missing. Maybe I just need to do more walking. Maybe even to Zuidas. But that is is all ahead of me. Back on the terrace of Het Nieuwe Diep, I order another beer. Cheers, Alan.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this, Will! And you’re definitely more Amsterdams than me. Looking forward to catching up when I get back - I might need these newfound local tour guide skills of yours to point out some city highlights. x Ingrid